June has come to an end. Every year for more than 50 years, this month has marked an important time in the fight against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, with the organization of “pride” marches and events all over the world. As an extension of Pride month, Notre Affaire à Tous looks back on the links between the climate justice and the LGBTQIA+ movements in a new special issue of IMPACTS, its magazine highlighting the consequences of climate change and the inequalities of their impacts.

The LGBTQIA+ movement stands as a testament to the power of collective action and the pursuit of equality and acceptance for all individuals, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Born out of a rich history of struggle, resilience, and activism, the movement has evolved into an international phenomenon that continues to make significant strides towards inclusivity.

The origins of the LGBTQAI+ movement can be traced back to the early 20th century when courageous individuals began challenging the societal norms and oppressive laws that marginalize sexual and gender minorities. However, it was the events of June 28, 1969, known as the Stonewall Riots, that ignited a spark that would shape the course of LGBTQIA+ history. The Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City, became the epicenter of a resistance movement when patrons fought back against a police raid. This uprising marked a turning point, galvanizing the community and leading to the emergence of LGBTQIA+ activism on a broader scale.

Building upon the momentum generated by the Stonewall Riots, the first official Pride march was held in the United States on June 28, 1970, commemorating the first anniversary of the uprising. Marsha P Johnson, a black, self-identified drag queen and activist, is now recognized as a leading figure in the Stonewall Riots and went on to become a symbol of LGBTQIA+ activism.

Marsha P Johnson, a trans, black woman and activist is now recognized as a leading figure in the Stonewall uprising and has now become a symbol of LGBTQIA+ activism.

« Portrait of Marsha P. Johnson, Freedom Fighter » by andydr is marked with CC0 1.0.

A couple years later, across the Atlantic, the French LGBTQIA+ community organized their own demonstration, the very first « Marche des fiertés » in Paris on June 25, 1977. Less known than the American equivalent, the 1977 « Marche des fiertés » was also one of the first initiatives for the European continent and the world.

The first LGBT Pride March, June 25, 1977 in Paris. (ANNE-MARIE FAURE-FRAISSE)

(Source: FranceTV Info)

This march was led by the Mouvement de libération des femmes (MLF) and the Groupe de libération homosexuelle (GLH) and gathered 300 protestors. Marie-Jo Bonnet, one of the participants of the 1977 march shared in an interview for FranceTV that the event was the very first time LGBTQAI+ people were bluntly and proudly visible in the country. She goes on to highlight the deep interconnections between the emerging queer movement of the 70’s and the already-well established feminist movement of the 30’s and 60’s (1) :

“It was a demonstration of women, there were very few men […] It was a feminist action above all. The idea of demonstrating had been transmitted by the women of the MLF, and in particular the homosexuals present within the movement.” (2)

Marie-Jo Bonnet, historian and feminist activist

Picture: Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Since those pioneering events, Pride marches have expanded exponentially, both in terms of geographic reach and participant numbers. Over the years, the LGBTQIA+ movement has gained visibility, mobilizing diverse communities and allies to advocate for LGBTQIA+ rights. The evolution of Pride is not limited to the United States and France; it has become a worldwide phenomenon, with cities across the globe hosting their own Pride events. From London to Sydney, Sao Paulo to Tokyo, an estimated 20 millions globally take to the streets to celebrate love, diversity, and equality.

Nevertheless, the Pride movement traces its roots in a fight against injustice. At the time of Stonewall, the movement emerged from Black and Brown trans and gender non-conforming people’s advocacy against police violence (3), and despite what are now worldwide celebrations, too many countries still inflict a systemic violence upon their LGBTQIA+ citizens. Many are still unaware of the exacerbated inequalities that the LGBTQIA+ community faces; at school, at work, or in the face of justice and climate change. For Notre Affaire A Tous; this edition is an opportunity to engage in a queer and feminist perspective of ecology and to reiterate its fight for social and climate justice. We hope that this edition will humbly participate in the fight that previous generations have undertaken; and will give voice – through the prism of the climate question – to communities that are too often overlooked.

Climate inequalities: the LGBTQIA+ community among the first to be affected

LGBTQIA+ people are affected by climate inequalities. They are among the populations particularly at risk from the impacts of climate change because of discrimination and violations of their fundamental rights. They also face specific difficulties that are not taken into account by public policies, making them even more vulnerable.

Discrimination and access to decent housing: risk factors in the face of climate change and environmental pollution

LGBTQIA+ people are among those most affected by the impact of global warming, primarily because of their housing situation. Worldwide, according to the OECD and the World Bank (4), LGBTQIA+ people are over-represented among those living in poverty, with the economic situation having a clear impact on access to and quality of housing.

While there are few studies in France, researchers in the English-speaking world have shown that LGBTQIA+ people are overrepresented among the homeless and unhoused, with their gender identity or sexual orientation leading to a break with their family networks or causing discrimination that makes it more difficult for them to access housing. In the United States, a study estimated that young people aged 18 to 25 who identified as LGBTQIA+ were 2.2 times more likely to be living on the streets than young people of the same age who identified as heterosexual (5). In France, the Fondation Abbé Pierre, in its 28th report on inadequate housing published in February 2023, points out that LGBTQIA+ people are often discriminated against in the workplace and on the housing maket, which leads to queer individuals being statistically more badly housed or homeless (6). Poor housing and homelessness are synonymous with a lack of protection or limited protection from bad weather or extreme heat, difficulties in accessing water (for drinking, washing, cooking, etc.), difficulties in accessing energy (and therefore both heating and the equipment needed in the event of a heatwave, such as refrigerators), and so on. The poorly-housed in France, including numerous LGBTQIA+ people, are therefore on the front lines when it comes to the impact(s) of climate change.

Poor housing conditions also have a significant impact on people’s health (7). Santé Publique France has already identified the correlation between poor housing and deaths during heatwaves (8).

Poorly-housed people are more likely to have health problems than those who are well-housed. These health problems then make people even more vulnerable to the consequences of global warming, creating a true vicious circle. Many chronic diseases (i.e. cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, allergies, asthma, mental health, etc.) are also exacerbated by climate change and its consequences (9). And this while LGBTQIA+ people are already statistically more exposed to mental health problems such as depression or anxiety; sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV; addictions; and that they suffer discrimination during their medical care experiences (10). The vicious circle of health problems caused by global warming is therefore exponential for LGBTQIA+ people.

The consequences of extreme weather events: an increase in anti-LGBTQIA+ violence

When it comes to extreme weather events, people who identify as LGBTQIA+ are generally at a disadvantage compared to people who identify as heterosexual. Firstly, because the discrimination they experience is an obstacle to effective protection against the impacts of climate change. Discrimination in recruitment, difficulties in integrating due to prejudice, health problems linked to difficult life paths, etc., have an impact on the economic situation of people who do not always have the means to move house, renovate their home, or rebuild it after an extreme weather event.

When an extreme event occurs, LGBTQIA+ people may be denied access to shelters or other assistance because of their gender identity or sexual orientation. This was the case, for example, following the earthquake in Haiti in 2020 (11). But these issues are also emerging in countries where recognition of the rights of LGBTQIA+ people is more advanced. Studies carried out in the United States have shown that LGBTQIA+ people were victims of violence and/or marginalisation following hurricane Katrina in 2005 (12). Trans people were denied humanitarian aid due to the lack of identity documents that matched their current gender and name, while same-sex couples were not considered families by federal agencies limiting the aid they received – usually to the detriment of their children – due to the agencies’ definition of the term « household » (13). Added to this is the difficulty of accessing medication or taking account of their particular problems.

In post-disaster situations, LGBTQIA+ people are more likely to experience harassment and violence, including physical violence (14). During the 2011 floods in Australia, 43% of people who identified themselves as LGBTQIA+ said they feared for their safety in the streets, parks, and evacuation centres (15).

Once again, the studies carried out in France on the consequences of extreme weather events, their impact, and the aftermath for LGBTQIA+ people are very limited, leading to a real invisibilisation of the issue (16).

Climate displacement and migration: discrimination throughout the migration process and a lack of real protection for LGBTQIA+ people

Global warming is also causing major population displacements: both as a result of sudden extreme weather events (floods, forest fires, storms, etc.) and long-term phenomena (desertification of certain regions, rising sea levels, etc.), people are being forced to leave their homes. The World Bank estimates that there will be 216 million climate-displaced people by 2050 (17). Because of their vulnerability to the consequences of climate change, LGBTQIA+ people are more likely to have to flee in order to survive. The discrimination they face puts them at even greater risk (18). In the course of their migration, they may suffer violence and abuse because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. Arriving in a new community may lead them to experience further discrimination and violence. They may also have no choice but to cross a border into a state where homosexual relations or their gender identity are criminalised (19), and sometimes even punishable by death (20). They then run a high risk of persecution. If they finally arrive in Europe or France (which is the case for a small percentage of exiles, most of whom settle in countries bordering their country of origin (21)), they risk deportation due to the lack of protection and « climate refugee » status.

LGBTQIA+ people face particular issues and significant discrimination that make them highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, as well as to mitigation and post-disaster aid policies and practices. Despite their importance, these climatic inequalities are little studied at a global level, and even less so in France. Yet more and more activists are showing that there are strong links between climate issues and the fight against discrimination against LGBTQIA+ people.

10 LGBTQIA+ activists for climate and environmental justice

LGBTQIA+ and ecological struggles still converge to a limited extent in France, but in English-speaking countries, notably the United States, and in so-called « South » countries, many LGBTQIA+ climate and social justice activists are visible and influential, whether in associations or other civil society movements, political organizations and/or on social networks. They all claim, more or less explicitly, an intersectional approach.

Here are 10 of them, presented in alphabetical order.

Deseree Fontenot (she/her, they/them)

Deseree is co-director of the Movement Generation : Justice and Ecology Project, which educates hundreds of organizations and individuals about ecological justice issues through the lens of relationship to land, ecosystems and interactions between individuals and communities spread across the United States.

Deseree also co-founded the Queer EcoJustice Project in 2016. This platform showcases collaborative projects blending ecological justice and LGBTQIA+ rights, in order to create a pool of resources and a community around these topics. For example, the Rhizomatic project seeks to understand the links between queer and environmental movements through interviews that highlight LGBTQIA+ environmental activists and the emergence of this movement. The project also aims to present a « counter-memory » to past movements, by making visible queer struggles that were previously unhistoricized and unrecognized. Finally, the project aims to suggest possible strategies for environmental organizations to build more diverse movements.

She currently works at the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies in Religion and Ministry in Berkeley, California.

Gabriel Klaasen (he/they)

Gabriel lives in Cape Town, South Africa, where he is coordinator of the African Climate Alliance, a youth movement born in 2019 after the first large-scale climate protests in South Africa. This movement calls for true intersectional climate justice and is developing a network of organizations and young activists across Africa.

Gabriel is also in charge of communication for the organization Project 90 by 2030, which pursues the same objectives. In particular, he has helped bring recognition within the South African climate movement of how the intertwining crises of social inequality and climate disruption are having a greater impact on the Most Affected People and Areas (MAPA), such as Black Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) communities, and LGBTQIA+ people. He also highlighted the major role of these populations in building a more desirable future.

Isaias Hernandez (he/him)

Isaias is a Mexican-American eco-influencer living in California. With a degree in environmental science, he uses social networks to speak in an accessible way about environmental justice, veganism and zero waste lifestyles. He also addresses climate inequalities, particularly those experienced by poor, racialized and/or LGBTQIA+ communities. Having been confronted with these inequalities himself, he wishes to offer a safe space for discussions via his social networks.

You can follow him on Instagram @queerbrownvegan, Twitter @queerbrownvegan and TikTok @queerbrownvegan. His website, Queer Brown Vegan, also offers many resources.

Izzy McLeod (they/them)

Izzy lives in Cardiff, Wales. On their blog The Quirky Environmentalist and their social networks, they link ecological issues, inequalities and LGBTQIA+ rights. In particular, they deal with fashion, defending a system that is sustainable for the planet and does not exploit the workers involved in the production line. In particular, in 2019 they launched the « Who made My Pride Merch » campaign, which calls on brands claiming to support LGBTQIA+ people to be more transparent about the conditions under which their products are made and to better protect workers’ rights, as the latter are particularly vulnerable and exploited in countries where they have few or no rights.

Izzy also seeks to put people from marginalized communities in the spotlight on their networks, to reveal the inequalities they suffer, and to discover and learn about different ways of being in the world.

In addition to their blog, you can follow Izzy on Instagram @muccycloud, Facebook Muccycloud and Twitter @muccycloud.

Jerome Foster II (he/they)

Jerome is the youngest member of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, since 2021. In 2019, he spoke about the climate crisis before the UN High Commission for Human Rights and the House of Representatives Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, among others. The same year, he organized climate strikes for the Fridays for the Future movement in front of the White House.

He also founded an organization, OneMillionOfUs now Waic Up, which seeks to engage young people in civic life and inform on issues such as gun violence, climate change, immigration, gender and racial equality.

In 2022, Jerome and his partner, Elijah McKenzie-Jackson, another climate activist, wrote a letter to the UN calling on the international institution not to hold COP27 in Egypt due to the infringement of LGBTQIA+ and women’s rights.

You can also follow Jerome on Twitter @JeromeFosterII, Instagram @jeromefosterii and TikTok @iamjeromefosterii.

Mitzi Jonelle Tan (she/they)

Mitzi is a Filipino environmental activist who focuses on climate justice issues – particularly between « Northern » and « Southern » countries – in a country that is highly vulnerable to climate change (typhoons, floods…) and particularly dangerous for activists.

In 2019, she co-founded the organization Youth Advocates for Climate Action Philippines (YACAP), the Philippine equivalent of Fridays for the Future, which calls for concrete, systemic action to address the climate crisis, protect environmental defenders and work for climate justice. She is also involved in the Fridays for the Future International and Fridays for the Future MAPA (Most Affected People and Areas) movements, where she campaigns for anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism and the intersectionality of the climate crisis. She encourages young people in « Southern » countries to get involved in local and international organizations, and in political processes.

You can follow Mitzi on Instagram @mitzijonelle and Twitter @mitzijonelle, and YACAP on Facebook Youth Advocates for Climate Action Philippines, Twitter @YACAPhilippines and Instagram @yacaphilippines.

Natalia Villaran (she)

Natalia is an Afro-Caribbean ecofeminist and artist living in Puerto Rico in the West Indies. She also claims an intersectional approach,.

Natalia is involved in the #Queers4ClimateJustice (Q4CJ) movement launched in 2018, which calls for the role of LGBTQIA+ communities, particularly vulnerable to the consequences of climate change, to be recognized by environmental movements. As an organizer of Q4JC, she notably made it possible to raise the issue of LGBTQIA+ inclusion with climate justice activists in Puerto Rico. It also enabled LGBQTIA+ people from Puerto Rico to attend the 2023 Creating Change national conference in San Francisco. The latter is organized annually by the National LGBTQ Task Force to advance justice and equality for LGBTQIA+ people in the United States.

Finally, in 2022, Natalia published her first book, Desamor y Memorias de una Virgo (The Heartache and Memories of a Virgin), a testimony about her experience as a racialized woman.

You can follow her Instagram account @queers4climatejustice and visit her website.

Pattie Gonia (she/they) / Wyn Wiley (he /him)

Pattie Gonia is a drag queen created by nature-loving photographer Wyn Wiley. Pattie Gonia’s approach is one of social justice and environmental activism. She is known for drawing attention to environmental damage through her messages and outfits, such as dresses made from plastic waste, leaves and other materials. Her account now brings together a community of queer people and allies sympathetic to ecological issues and passionate about nature expeditions.

You can follow her on Twitter @PattieGonia, Instagram @PattieGonia et YouTube @PattieGonia7449.

Precious Brady-Davis (she/her)

Precious is a transgender woman living in Chicago. She is a consultant on diversity, equity and inclusion issues, and associate regional communications director for the Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, which wants to close all coal plants in the U.S. to replace them with renewable energy sources. She was appointed in 2023 to Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s Transition Subcommittee for Human Rights, Equity and Inclusion.

Precious is also a speaker and author of the book I Have Always Been Me, published in 2021, which talks about her childhood and journey as a transgender woman of color.

You can follow her on Instagram @preciousbradydavis and Twitter @mspreciousdavis.

Tori Tsui (she/they)

Tori is a queer eco-activist from Hong Kong currently living in the UK. She co-founded the Bad Activist Collective platform, which brings together intersectional activists for racial justice, climate justice and LGBTQIA+ rights through art and activism. In particular, Tori deals with mental health and environmental catastrophism. In July 2023, she will publish It’s Not Just You, which explores the relationship between the climate crisis and mental health. In this book, she calls for a collective approach to « eco-anxiety », rather than individualizing it, in order to question the role of the socio-economic and political system in the development of that « anxiety ».

She took part in a project called « Sail For Climate Action », aimed at giving a voice to young people from Latin America, the Caribbean and indigenous communities, in order to better represent these invisibilized regions and communities, while they are among the first to be affected by the consequences of global warming. With other climate activists, she has also launched a campaign called « Pass The Mic », which aims to get influential personalities and brands to highlight climate justice activists and people already particularly affected by the climate crisis.You can follow Tori on Instagram @toritsui_, Twitter @toritsui, TikTok @toritsui, and visit her website. You can also follow Bad Activists Collective on Instagram @badactivistcollective.

Vani Bhardwaj’s interview

Vani Bhardwaj

Ph.D. candidate at the Indian Institute of Technology, Guwahati, India. Co-Lead of the Gender and Climate Justice Circle at Society of Gender Professionals. Head of Policy at Young Women In Sustainable Development. Researcher for The Pixel Project focused on gender-based violence projects and campaigns. Author of Queering Conflict Transformation and Peace-building and Queering Disasters In Light Of the Climate Crisis for the Gender in Geopolitics institute.

In this next section, Notre Affaire a Tous was lucky to learn from Vani Bhardwaj, who took the time to answer our questions. Vani is pursuing her PhD about Climate Change and Gender Intersectionalities, focusing on how women and the queer population in India and Bangladesh are impacted by transboundary water politics. In addition to being a full time PhD student, Vani also takes part in different volunteering initiatives which focuses on gender and climate change, notably with both global and local queer feminist organizations.

Vani has kindly agreed to share her expertise with Notre Affaire à Tous, so to preserve the academic authenticity of her words and work, and to maintain the integrity of the people she lends her voice to, this interview will be rendered as closely to the discussion as possible.

Notre Affaire à tous (NAAT) : How do you think the experiences of LGBTQIA+ people, queer individuals intersect with environmental concerns and climate change impacts?

Vani Bhardwaj (VB) : I believe environmental change is now known to have an exaggerated impact for women and girls, but what often gets omitted is that the queer population is also completely ostracized – there is a “queer blind narrative” around ecology and how we approach ecology. So in order to incorporate the queer population within our climate change narratives, we need to reframe the way we understand ecology itself. For instance, when we look at public spaces that are somewhat “taboo” – which are ostracized, or at the outliers of a city or even a rural hinterland – that is very similar to the way the queer population is treated in India.

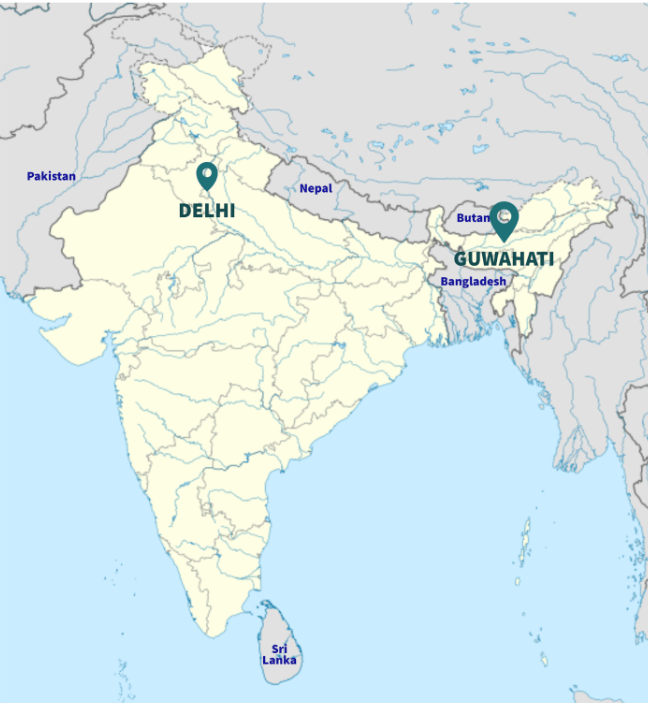

So when we look at, say, climate disasters, and we think of restabilizing the lives of the people afterwards, we never cater to the queer population. And there are particular intersectionalities that even the queer population is not really acknowledging themselves. I once talked to a queer person living in Delhi [capital of India] which observed a certain position of power compared to people living on the periphery of the country, like Guwahati [city in North-East India, between Bangladesh and Bhutan], the city I am located as we speak. Guwahati is home for Dalit people [i.e. lowest caste in India, “outcastes” and “underprivileged”) and when I addressed the conditions of life for Dalit queer people, the person living in Delhi completely denied the terms “Dalit queers” stating that the queer population itself is not “casteist”, it does not have caste-based discrimination. But that is not true, when we look not only at literature but also lived experiences of many Dalit scholars, they talk about how even the “Dalitality” (a concept attributed to Dr. Suraj Yengde) actually matters in everyday lives: Dalits are ostracized, and discriminated against when it comes to their career just on the based off caste, so they are doubly marginalized if that individual is Dalit and queer.

There is some kind of a blind spot within the Queer community regarding that. So when this Dalit queer individual was embedded in such a society, faces displacement due to climate disasters, which are caused by climate change, they are doubly and triply marginalized. They are almost silenced in the mainstream narrative, and I think that is why it is very crucial to focus on the queer narratives within the climate change impacts, and not only impacts, but consequences as well. We really need to reframe how we approach ecology as such and I think the particular stance of queer feminist political ecology is the most inclusive frame.

NAAT : Are there any specific initiative, policy or advocacy efforts that have emerged from the collaboration between queer and ecological movements you can think of and how effective have they been in addressing the concerns and claims of both groups ?

VB : I would say that the convergence of climate change issues and the queer population is really not clear in India. Living and working in a place which itself is at the periphery in India, we are already trying to normalize the narrative that people are not to be ostracized, because the narrative against LGBTQIA+ population is very much prevalent in the peripheries. We are still working on normalizing the fact that we are also human you know. That’s the kind of narrative that we need to normalize first.

I think the convergence between climate change issues and how it is exaggeratedly impacting LGBTQIA+ population has not really taken off in small Indian towns, it is much more prevalent in Mumbai or Delhi, which are the metro cities of the country. But in my own activism I have created a global and online community of practice approach in which we do invite grassroots scholars and academia together so people who are theoretically engaged in this space and who are practically on the ground, implementing and designing climate adaptation-related projects can come together and have these dialogue sessions. Many times when we talk about gender and climate justice frameworks, we have queer political activist from outside of the periphery who say that we need to go beyond these dialogue sessions but I think the ground realities are very different from the theory, particularly in Guwahati where the inclusion narrative has not really emerged. A local convergence of activism is not relevant and is almost ahead of its time in that sense.

« India location map » by Uwe Dedering at German Wikipedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

NAAT : What are some of the challenges or barriers faced by people either from the Global South, from the periphery, or even more locally in Guwahati in engaging with climate justice movements, and how would you say these challenges differ from the ones from the Global North or “Centre”?

VB : So first of all, if we look at it from a scholarly and theoretical manner, I always find it difficult to find any kind of literature regarding climate justice, queer population and their intersectionalities being explored in the “majority world’s academia”. Most, if not all the research available, usually comes from scholars from South Africa or Australia exploring the intersectional relations between the Global South and the queer population(s) getting impacted by climate change and climate disasters. In addition to being scholarly and theoretically limited, in a practical approach and real ground realities, when you do your ethnographic research and when you go to different households, you can’t expect a closeted person who has not come out yet to just be vulnerable to you outright for the sake of research. There is an inherent and prevalent patriarchy, transphobia and homophobia on ground realities within rural Bangladesh or India.

Picture this, the Brahmaputra river is flooding year after year, and we want to talk about disaster relief efforts with locals. What we see is that there is no sex disaggregation or gender disaggregation based data and there is a high degree of chance that people who have not revealed their sexual or gendered identities, and are part of a minority, may again be at a disadvantage because the shelter camps and post-disaster recovery efforts are completely blind to gender. They are blind when it comes to women and girls so they are also completely blind about queer populations.

For queer communities, there’s a concept of housing, and then there’s a concept of home, right? Where exactly is “home” is a question many queer people problematize and wonder their entire lives. If they do not have the support within their families, which without the intention to do a generalization is very often the case in hegemonic heteronormative families in India and Bangladesh. That creates settings that are transphobic and/or homophobic, and it becomes very difficult for people to come out to their own family. The entire concept of home becomes irrelevant, they feel alienated inside their so called home, and so they try to find community and networks outside of their bloodline. That is to say that in situations of climate disaster, it is not automatically their home being taken away, it is more their housing if they have one.

Lots of queer people in India will battle this trauma and this internal conflict of what really is “home” their entire lives and I think that wound reopens when climate disasters keep striking again and again. It is kind of a double or a triple displacement, a displacement at the social, economic, psychological and psychosocial level. I think the government has particularly been very much blind up until 2-3 years ago to the fact that queer population even existed when climate disasters happened because there is a very apparent transphobic and homophobic attitude within disaster relief volunteers themselves which participates in ostracizing the queer community when it comes to disaster relief efforts. And where I’m living, in the periphery of India, a very marginalized place in itself, climate disasters are very normalized events, striking very often. So people are “used” to these climate-related disasters. But if we look at the disparities of class and their related issues, the most vulnerable people are getting displaced repeatedly, and they really don’t have economic stability.

So in this part of the country, when climate disaster strikes, not only does hegemonic masculinity and femininity get affected, but we also observe that indigenous masculinity and indigenous femininity get swept away in the disaster too. They get swept away in the disaster, in the sense that for example indigenous masculinity gets challenged as they no longer are the breadwinner of the household because of the climate disaster. So amongst all of these complex notions for a queer individual to even come out, and, you know, reveal “I am part of the queer community and I have exaggerated impacts due to the climate disasters” is quite difficult. In addition, asking the government for measures or policies, or to simply have queer activists sitting on the round table for policy making that is even more of a challenge.

The Indian civil society is trying to eliminate transphobia and homophobia through pride marches and push for community networking spaces like open libraries for queer community-members to come, sit and read together. More of these initiatives are emerging but intersectionality with climate change still hasn’t been mainstreamed because queer people are missing in the public policy-making spaces dedicated to disaster management policies.

Frankly, heteronormative people are not going to sit there and you know, be so much as sensitive regarding the queer population’s relation to climate disasters while they’re transphobic and homophobic in their private sphere. We really need the queer population to actually be part of that policy circle which decides disaster management policies. And I think because the indigenous masculinity and indigenous femininity also get challenged by climate disasters, and within that, we need to find this queer narrative to challenge these multidimensional marginalities in relief efforts.

NAAT : What role do you think intersectionality plays in the relationship between the climate justice movement and the LGBTQIA+ movement, and how does it change the experiences and priorities of individuals who identify as part of both groups?

VB : First, let me make it clear that the LGBTQ+ community is not homogeneous so we need to recognize the heterogeneity of the community. Then secondly, we need to ensure that the spaces in which the community is embedded are comfortable so that it becomes comfortable for individuals to reveal their place on the entire sexual and genital spectrum, which is still very much of a struggle, at least in India, as I can’t speak for the entire Global South.

For instance in India, there’s a great difference and disparity between how much the lesbians and the gays get discussed in mainstream queer narratives, and how much the asexuals are completely marginalized. They are basically the “plus” in LGBTQ+. So obviously there are always differentiations but no categorization, because the moment you categorize anything, then you are endangering the entire community to exclusion. The moment you start categorizing, you are essentially trying to exclude somebody. So the moment you’re trying to set boundaries by categorizing by putting a nomenclature, you are bound to exclude somebody or the other.

And I think that is how climate justice narratives and activism need to incorporate everybody within the LGBTQs if you really want to have a separate networking or like a separate community or civil society organization focusing only on lesbians then another organization focusing only on transgenders, those can be separate, because they don’t have these separate differentiated demands , although they do have a common thread of getting ostracized multidimensionally. So it is very much essential for LGBTQ population because.

When a climate disaster strikes, what happens is that whatever landscape that has been established completely gets dismantled and you have to rebuild it once again. So in that same way, when we’re talking about gender and sexuality spectrum, I think we can completely dismantle the way we have been heteronormative in discussing it and we can rebuild all of that. Climate disaster recovery and recovering and gender narratives are very much closely linked together.

There is this entire strand of queer feminist political ecology that talks about how the so called “unkempt and the pristine” forests that have not been touched, that are at the outsides and the outskirts of the city, or the towns which are basically the embodiment of the ostracized – where nobody is living. Those are places which the local queer community can completely relate to, because of a shared sense of ostracization. Queer political ecology is how ecology is being understood by the queer population, how the queer community experiences the environment, how they experience ecology, how they experience, you know, the flow and flood of the river within the city or the polluted air around them? You know we only have cis-heteronormative and capitalistic narratives about our understanding of the environment. I remember like in primary school we were taught that there are biotic and abiotic components and so there are always binaries, there is the normal life and then there is the disrupted life due to climate disaster so that’s again a binary. But if you really look at the queer activists and how they will see a climate disaster or even climate change, maybe it won’t be that much in a binary context, it won’t be so dualistic in classification and categorization and that is why would benefit from more trans and queer scholars to understand environment itself; we need to reframe how we understand the concept of environment itself. We need to go to the basics and unpack those to really dovetail queer activism with climate change and climate justice.

NAAT : Climate movement(s) in France have lacked the perspective of the periphery in both academic circles and mainstream narratives. Would you have any recommendations for “Global North » countries and organizations to 1) better include the “Global South”, or rather the situated knowledge(s) and local experiences within international climate justice movements, and how can the Global North better include LGBTQIA+ people in their climate justice initiatives?

VB : Thank you for that wonderful question. I think it has many parts to it. So let me just talk about this classification of Global North and Global South and the moment you say Global North and South, they’re juxtaposed into binaries and it becomes “Global North” versus “Global South”. Or at least that’s what it comes off as in more general settings. Whenever I use those terms, they are defined by power dynamics and positionality. So most people have now started saying “majority world” instead of Global South, but I refrain from even using that because when you use “majority world” that it itself shows a very majoritarian thinking. You know, trying to do like a reverse discrimination that if you colonized us with a certain perspective or approach, we’re going to reverse the power hierarchy. So I don’t think we have found the particular terminologies to reflect this complexity yet, whether it should be “Global South” or “majority world” or “periphery”.

But I think as far as including localized narratives and knowledge within the LGBTQ and climate activism, in the Global North or the South, we need to have localizing vernacular language-based climate justice narratives. So even if you see global organizations or even local and national organizations, they are mainly dealing with the dominant language. For example, if an Assamese queer civil society organization approaches the climate justice perspective they would still frame their ideas and their advocacy in the dominant language, which is Assamese – and most probably English – but these are the 2 dominant languages of the state. These are not the only languages, we have hundreds and thousands of languages within a few 1000 kilometers so I think to really localize climate justice impacts on queer populations and even for women and young girls, what we really need to do is to make the entire queer and climate advocacy toolkits, and implementation guides, and scholarly literature very much localized and embedded in vernacular languages. And that is something that is also missing at the global level in the sense that when you are talking about voluntary national reviews and.sustainable development goals and “not leaving anyone behind” – what we’re really doing pushing the ostracization as we’re not having an audit or we are not conducting vernacular language based voluntary national reviews. If they are all dominant language based, the language becomes an issue.

To say that Global North and Global South have completely juxtaposed to each other is also correct. Wendy Harcourt talks about how there are “margins within the centre” and periphery within the Global North. Global North is not a homogeneous entity itself. There are margins so we can create solidarity from the margin in Global South to the margin and periphery in the Global North because we also have power dominant and hierarchical places within the Global South who try to completely suppress the voices of the periphery in our countries. I think creating solidarity from the periphery in the Global South to the periphery in the Global North is what we’re really looking at when we’re talking about climate justice solidarities from queer population across the spectrum.

Conclusion

The climate and ecological issues still inadequately consider the experiences of LGBTQIA+ individuals, the specific challenges they face, and the discriminations they endure. This creates a blind spot, a gap, in the study of the impacts of climate change and pollution. Consequently, climate and ecological policies, as well as post-disaster aid, reinforce existing inequalities and discriminations. For a just ecological transition, it is urgent to consider the multiple forms of discrimination, including those against LGBTQIA+ individuals, who are particularly vulnerable to climate and environmental risks, as we have seen in this special issue.

Several actions can be taken to make public policies more inclusive. For example:

- Develop data collection and research on the consequences of climate change for LGBTQIA+ communities to better meet their needs.

- Evolve the practices of recognizing refugee status and rethink the reception of LGBTQIA+ individuals, including the practices of the OFPRA and the CNDA regarding evidence of persecution based on sexual orientation and gender identity. This would enable better access to refugee status for LGBTQIA+ individuals facing discrimination and violence due to their sexual orientation and/or gender identity resulting from extreme climate events or other factors that have forced them to flee.

- Improve information and participation of LGBTQIA+ individuals in decision-making processes related to climate change and environmental issues.

- Strengthen and expand health-environment plans to include the unequal impacts of climate change on certain segments of the population, including LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Including LGBTQIA+ environmental activists in environmental movements, both in the Global North and the Global South, is extremely important as they often intrinsically and tangibly connect the fight for environmental and social justice. This could be beneficial for current environmental movements that increasingly claim, at least in their discourse, to act for a socially just ecological transition.

Considering the specific difficulties faced by LGBTQIA+ individuals in the consequences of climate change would also allow environmental movements to propose more inclusive alternatives to the current system. However, this requires making these difficulties visible and known within activist circles and, more broadly, moving away from heteronormative narratives that are often binary and unquestioned due to being perceived as « natural » while being social constructions. Documentation and awareness-building work is thus necessary within environmental movements themselves.

One potential approach could be to place LGBTQIA+ environmental activists and other marginalized communities who are still too invisible, especially in Europe, at the forefront of ecological movements. In particular, giving a voice to, listening to, and learning from activists from the Global South would be a tremendous enrichment for environmental and social movements, expanding our worldview, raising awareness of diverse situations and life experiences, and shedding light on the many interconnected inequalities communities across the globe suffer from. As Global South communities are both the least responsible for climate change, and yet the first victims of its impact, they ought to be included to envision more inclusive and more relevant solutions.

Lexicon

Asexual: Someone who experiences little or no sexual desire.

Binary: The term refers to the two gender identities that have long been recognized in Western societies (male and female). This is in contrast to the term « non-binary, » which includes all gender identities (transgender, intersex, etc.)

Bisexual: Someone who experiences attraction to both binary genders, male and female.

Cisgender: A person whose assigned sex at birth matches their gender identity.

Gender Disphoria: Distress and suffering related to the discrepancy between a person’s assigned gender and their gender identity.

Gender Fluid: Someone whose gender identity and/or sexual orientation varies over time.

Gay: A man who experiences sexual or romantic attraction to other men.

Global North and Global South / Center and Periphery: The notions of Global North and Global South are not based on the geographical position of the countries they qualify.

- The Global North refers to countries, admittedly primarily located in the Northern hemisphere, that have historically been identified as “the West” or “the first world” due to the geopolitical power dynamics these regions benefit from. This dominance is exercised through the prism of the neo-liberal capitalist system; and is expressed with relative wealth, advanced technologies, a past of colonial empire, all often associated with a hegemonic context.

- As for the term “Global South”, it is attributed several definitions. The Global South has traditionally been used to refer to so-called “third world”, “underdeveloped” or “economically disadvantaged” nations. These countries have historically been colonized by the countries of the North (in particular by European countries). The term “Global South” is also used to describe populations that are negatively affected by capitalist globalization. Although the use of the term “Global South” has become common in academic circles, and due to its “essentialist” aspect, it is often criticized and described as confusing, inaccurate and possibly offensive depending on the context.

- For these reasons, researchers represented by this term employ it in juxtaposition with other concepts such as “the Periphery” (as opposed to the “Center”) which refers to the theory of economic dependence, or the “majority world ” (“majority world” in English) which highlights the large demographic majority represented by these countries.

Heterosexual: In a binary gender structure (male/female), being attracted to people of the opposite sex.

Homosexual: In contrast to heterosexuality, within a binary gender structure (male/female), being attracted to people of the same sex.

Homophobia: Hateful or contemptuous behavior or discourse towards homosexual individuals, and more generally towards LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Intersex: A person born with sexual characteristics (chromosomes, hormones, anatomy) that do not fit the binary definition of sexes.

Lesbian: A woman who experiences sexual or romantic attraction to other women.

LGBTQIA+: Acronym for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual, and any other sexual orientation or gender identity.

Pansexual: Someone who experiences sexual attraction to all genders, binary or non-binary.

Queer: Originally used as a derogatory term in English meaning « strange, » the word queer has been reclaimed by LGBTQIA+ individuals to embrace their differences. The term now refers to anyone who does not identify within the binary view of gender (male/female) and sexual orientation (hetero/homo).

Transgender: A person whose gender identity does not align with the gender assigned to them at birth.

Notes

- Feminism : feminist movements and struggles in History – Oxfam France

- En 1977, elles participaient à la première Marche des fiertés : « On était encore les anormaux » (francetvinfo.fr)

- Stonewall, Rebellion and Pride: How Police Fail LGBTQ+ Communities (naacpldf.org)

- World Bank – Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

- LGBT People and Housing Affordability, Discrimination, and Homelessness – Williams Institute (ucla.edu)

- Annual report from Fondation Abbé Pierre L’état du mal-logement en France 2023 (p. 53-54)

- See Santé Publique France :Le logement, déterminant majeur de la santé des populations. Le dossier de La Santé en action, n° 457, septembre 2021. (santepubliquefrance.fr) and Le mal-logement, déterminant sous-estimé de la santé. (santepubliquefrance.fr)

- Le logement, déterminant majeur de la santé des populations. Le dossier de La Santé en action, n° 457, septembre 2021. (santepubliquefrance.fr)

- See for instance the Climate & Health report from the French High Council on Public Health, the scientific article “Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews” and the note from the Canadian Association for Global Health “Climate change and chronic conditions : linkages and gaps”.

- See French press articles: Le Monde, “La santé des LGBT, un tabou médical” and Libération, “Le grand malaise des LGBTI face au monde de la santé”

- Queering Environmental Justice: Unequal Environmental Health Burden on the LGBTQ+ Community | AJPH | Vol. 112 Issue 1 (aphapublications.org)

- Queering Environmental Justice: Unequal Environmental Health Burden on the LGBTQ+ Community | AJPH | Vol. 112 Issue 1 (aphapublications.org)

- Sexuality and Natural Disaster: Challenges of LGBT Communities Facing Hurricane Katrina by Bonnie Haskell :: SSRN

- Queering disasters: on the need to account for LGBTI experiences in natural disaster contexts – CORE Reader

- Problems and possibilities on the margins: LGBT experiences in the 2011 Queensland floods: Gender, Place & Culture: Vol 24, No 1 (tandfonline.com)

- Queering disasters: on the need to account for LGBTI experiences in natural disaster contexts: Gender, Place & Culture: Vol 21, No 7 (tandfonline.com)

- D’ici à 2050, le changement climatique risque de contraindre 216 millions de personnes à migrer à l’intérieur de leur pays (banquemondiale.org)

- See example from trans people experiences : Migrer et être trans, la double peine. – ÉCARTS D’IDENTITÉ (ecarts-identite.org)

- SeeUNHCR communicate from 2022 : Forcibly displaced LGBT persons face major challenges in search of safe haven

- See communicate from Filippo Grandi (UNHCR) in 2021 : UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi’s message on the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia

- According to UNHCR, 70% of refugees are hosted by neighboring countries Figures at a glance